Black Scholes in PyTorch

Dec 9, 2018

I've been experimenting with several machine learning frameworks lately, including Tensorflow, PyTorch, and Chainer. I'm fascinated by the concept of automatic differentiation. It's incredible to me that these libraries can calculate potentially millions of partial derivatives of virtually any function with only one extra pass through the code.

Automatic differentiation is critical for deep learning models, but I wanted to see how it could be applied elsewhere. I've always been interested in financial derivatives like stock options, and calculating greeks (the partial derivatives of option price) can often be a slow process of running and re-running models repeatedly. The process gets even more complicated for complex, path-dependent options. As I found while writing this article, PyTorch can make this process much faster and more exact.

Goals for this article

The purpose of this article is to use PyTorch to implement four methods of calculating European put option price and greeks. I'll demonstrate how automatic differentiation can be used to calculate option greeks, and measure the time it takes for each implementation.

- Use the Black-Scholes formula and the closed-form equations for option greeks.

- Use the Black-Scholes formula and calculate option greeks using the "finite difference" method.

- Use the Black-Scholes formulas for option value and use PyTorch to automatically differentiate the output and calculate the option greeks.

- Use a monte carlo simulation of option values in PyTorch. Then use automatic differentiation to calculate option greeks.

A brief primer on European stock options:

A European stock option is a financial instrument that gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying security for a pre-determined price at a specific future date. It goes without saying that the future values of financial securities are uncertain. Therefore, options on those securities can be difficult to price.

There are plenty of resources available to learn about options, from the basics all the way through stochastic calculus and exotic option varieties. In fact, many of the techniques that I'm going to demonstrate become much more relevant and powerful for more complex options. However, for the purposes of this article I'm going to focus exclusively on a simple European put option. Fortunately, if we make certain simplifying assumptions, the European put option can be valued in closed-form using the famous Black-Scholes formula.

In addition to knowing the value of the option, it is also useful to understand how the value will change if certain assumptions change. In other words, it is useful to understand the partial derivatives of option value with respect to the inputs to the Black-Scholes formula. These sensitivities are typically called "the greeks". We'll use closed-form equations as well as PyTorch's automatic differentiation to calculate the greeks.

The Black-Scholes Formula

This is the formula we'll use to calculate the price of the European put option. There are formulas for each of the greeks too: delta, rho, vega, theta, epsilon, etc., but I'll spare the math for now.

where

- is the put option price

- is the stock price

- is the strike (exercise) price

- is the annual continuously compounded risk free interest rate

- is the annual volatility of the underlying security

- is the time to expiry in years

- is the annual continuous dividend rate

- is the standard normal CDF evaluated at

PyTorch setup

Like many deep learning frameworks available today, PyTorch provides high-performance numerical computation, automatic differentiation, and the ability to run on distributed grids of hardware accelerators, like GPUs. PyTorch computational graphs are created on the fly, as opposed to the static graphs you build in a language like Tensorflow. But both libraries provide automatic differentiation out of the box.

To enable automatic differentiation, we must identify the inputs to our formulas as tensors and start gradient tracking for those inputs. PyTorch will keep track of the operations on those inputs from the beginning to the end. Once we're finished with our computation and we have our output, we can run reverse mode automatic differentiation to calculate the gradient of the output with respect to each input.

Throughout this article, I'll use the following six input tensors and their defined values for the Black-Scholes formula. I'll also create two utility functions that we'll use as we go along.

# black-scholes inputs

stock = torch.tensor(100.0, requires_grad=True)

strike = torch.tensor(100.0, requires_grad=True)

rate = torch.tensor(0.035, requires_grad=True)

vol = torch.tensor(0.16, requires_grad=True)

time = torch.tensor(1.0, requires_grad=True)

dividend = torch.tensor(0.01, requires_grad=True)

# utility functions

cdf = torch.distributions.Normal(0,1).cdf

pdf = lambda x: torch.distributions.Normal(0,1).log_prob(x).exp()

Method 1: Black-Scholes Formula for Option Value and Greeks

The first method is purely formulaic. We'll use the Black-Scholes formula plus the formulas for all option greeks. PyTorch is certainly overkill for this method - we could use virtually any programming language to implement this.

# black-scholes formula

d1 = (torch.log(stock/strike) + (rate - dividend + vol*vol/2)*time) / (vol*time**0.5)

d2 = (torch.log(stock/strike) + (rate - dividend - vol*vol/2)*time) / (vol*time**0.5)

ov = strike*torch.exp(-rate*time)*cdf(-d2) - stock*torch.exp(-dividend*time)*cdf(-d1)

# black-scholes greeks

delta = torch.exp(-dividend*time) * (cdf(d1) - 1)

rho = -strike * time * torch.exp(-rate*time) * cdf(-d2)

vega = stock * torch.exp(-dividend*time) * pdf(d1) * time**0.5

theta = -(

rate * strike * torch.exp(-rate*time) * cdf(-d2)

- stock * torch.exp(-dividend*time) * pdf(d1) * vol / (2*time**0.5)

- dividend * stock * torch.exp(-dividend*time) * cdf(-d1)

)

epsilon = stock * time * torch.exp(-dividend*time) * cdf(-d1)

strike_greek = torch.exp(-rate*time) * cdf(-d2)

When we run this code with our inputs from above, we get the following table of outputs. This option price is $5.09. Plus, we can estimate how the price will change if any of our model inputs changes. For example, a Delta of -0.4026 implies that if the underlying security increases in value by $1 (from $100 to $101), the option price should decrease by roughly $0.40. Similarly, if we were to decrease the time-to-expiry of this option from 1.0 years to 0.9 years, we would expect option price to decrease by roughly 10% of the option theta, or 0.18883.

Option Value: 5.0885 # sensitivity of option price to:

------------------------ ---------------------------------

Delta: -0.4026 # underlying price

Rho: -45.3458 # interest rates

Vega: 38.4103 # volatility

Theta: 1.8883 # time

Epsilon: 40.2573 # dividend rate

Strike Sens: 0.4535 # strike price

Method 2: Black-Scholes Formula with Finite Difference Greeks

With most models, a simple way of calculating partial derivatives is to re-run the model many times with slightly different inputs and observe how the output changes with each new run. This is often called the "finite difference" or "bump-and-revalue" method. It doesn't require you to derive the greeks of the formula by hand - indeed this can often be impossible. This method provides an estimate of the true partial derivative, and is based on the following formula:

As an example, let's estimate put option delta using this method. We originally valued the option at $5.0885 (above), given a stock input of $100. If we re-run our model after changing stock to $101 and keeping everything else constant, the option price decreases to $4.6978. Then, according to the formula above, our estimate of delta is:

Let's implement this in code. Again, PyTorch is overkill here because we're simply using the same Black-Scholes formula from Method 1 and re-running it six extra times to calculate our option greeks.

# black-scholes formula

def bs(stock, strike, rate, vol, time, dividend):

d1 = (torch.log(stock/strike) + (rate - dividend + vol*vol/2)*time) / (vol*time**0.5)

d2 = (torch.log(stock/strike) + (rate - dividend - vol*vol/2)*time) / (vol*time**0.5)

ov = strike*torch.exp(-rate*time)*cdf(-d2) - stock*torch.exp(-dividend*time)*cdf(-d1)

return ov

# baseline option value and 1% sensitivities

ov = bs(stock, strike, rate, vol, time, dividend)

delta = bs(1.01*stock, strike, rate, vol, time, dividend)

rho = bs(stock, strike, 1.01*rate, vol, time, dividend)

vega = bs(stock, strike, rate, 1.01*vol, time, dividend)

theta = bs(stock, strike, rate, vol, 1.01*time, dividend)

epsilon = bs(stock, strike, rate, vol, time, 1.01*dividend)

strike_greek = bs(stock, 1.01*strike, rate, vol, time, dividend)

# scaling; in each case, δ is 1% of the starting value

delta = (delta - ov) / (0.01*stock)

rho = (rho - ov) / (0.01*rate)

vega = (vega - ov) / (0.01*vol)

theta = (theta - ov) / (0.01*time)

epsilon = (epsilon - ov) / (0.01*dividend)

strike_greek = (strike_greek - ov) / (0.01*strike)

We see that the option greeks from this method vary slightly compared to the exact formulas used in Method 1. This is because we can only approximate the partial derivatives through finite difference. I used 1% sensitivities, which is fairly standard. Smaller values, like 0.1%, would result in greeks closer to the exact values, but wouldn't reflect as much convexity in the option price. That is typically the tradeoff with the finite differences method.

Option Value: 5.0885 # sensitivity of option price to:

------------------------ ---------------------------------

Delta: -0.3907 # underlying price

Rho: -45.2968 # interest rates

Vega: 38.4164 # volatility

Theta: 1.8803 # time

Epsilon: 40.2069 # dividend rate

Strike Sens: 0.4654 # strike price

Method 3: Black-Scholes Formula with PyTorch Automatic Differentiation

Now the fun part. Before, we either had to carefully program complex formulas for option greeks (missing a negative sign here or there is a common and frustrating error), or re-run our model several times and scale the outputs. It's easy to make mistakes in either case.

Instead, let's start to leverage PyTorch's automatic differentiation. As before, we program the Black-Scholes formula (you'll notice the implementation is exactly the same). Once we have the option value, we simply call ov.backward() to tell PyTorch that we want to calculate the partial derivatives of our model. Because we tagged each input with require_grad=True, we can call .grad on each input to get its gradient.

# black-scholes formula

d1 = (torch.log(stock/strike) + (rate - dividend + vol*vol/2)*time) / (vol*time**0.5)

d2 = (torch.log(stock/strike) + (rate - dividend - vol*vol/2)*time) / (vol*time**0.5)

ov = strike*torch.exp(-rate*time)*cdf(-d2) - stock*torch.exp(-dividend*time)*cdf(-d1)

# run backpropagation to calculate option greeks

ov.backward()

delta = stock.grad

rho = rate.grad

vega = vol.grad

theta = time.grad

epsilon = dividend.grad

strike_greek = strike.grad

Each value in the table below is identical to our original calculations using Method 1. And I would argue that the code above is significantly simpler to write, read, and debug. Furthermore, I can be confident that the gradients are correct because I didn't have to input complex formulas by hand.

Option Value: 5.0885 # sensitivity of option price to:

------------------------ ---------------------------------

Delta: -0.4026 # underlying price

Rho: -45.3458 # interest rates

Vega: 38.4103 # volatility

Theta: 1.8883 # time

Epsilon: 40.2573 # dividend rate

Strike Sens: 0.4535 # strike price

Method 4: Monte Carlo simulation of stock prices with Automatic Differentiation

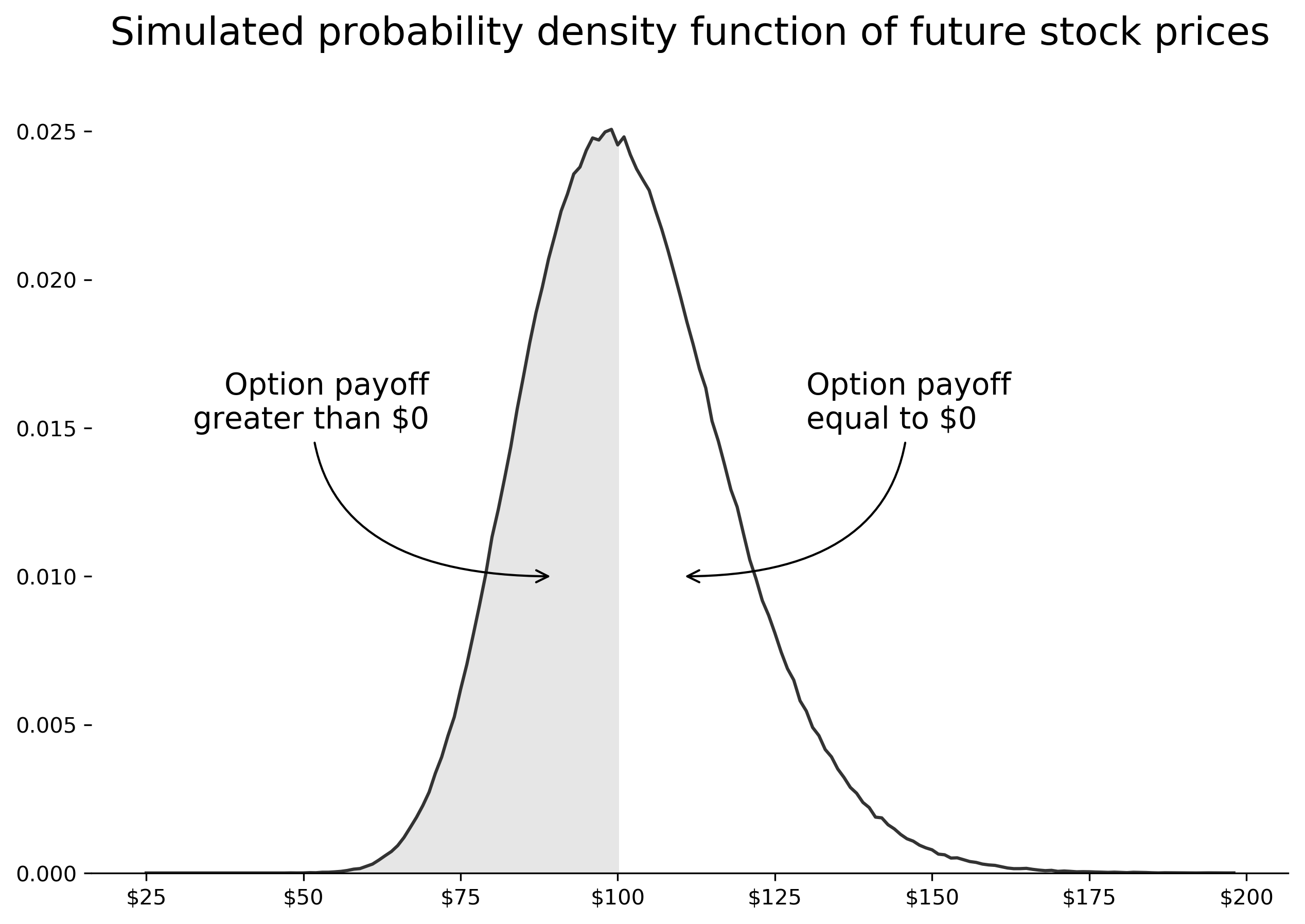

The fourth method is unlike the first three in that it doesn't use the Black-Scholes formula at all. Instead, it uses the principle upon which the formula is based, called Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM). GBM is a model for simulating future distributions of stock returns. It is a stochastic method, which means we'll draw thousands of samples from a normal distribution of stock returns in order to understand the potential future values of the stock on the exercise date.

Once we have several thousand randomly drawn future stock values, we simply calculate the option payoff under each scenario. We then discount the future payoffs to today and take the average value of all the scenarios we ran. If we run enough scenarios, then the average should converge to the Black-Scholes price of the option.

# geometric brownian motion (single time step)

torch.manual_seed(42)

scenarios = 1000000

dW = vol * time**0.5 * torch.randn(size=(scenarios,))

r = torch.exp((rate - dividend - vol*vol/2) * time + dW)

# put option payoff & discounting

payoff = torch.max(strike - stock*r, torch.zeros(size=(scenarios,)))

ov = torch.mean(payoff) * torch.exp(-rate*time)

# run backpropagation to calculate option greeks

ov.backward()

delta = stock.grad

rho = rate.grad

vega = vol.grad

theta = time.grad

epsilon = dividend.grad

strike_greek = strike.grad

Did you notice that we were able to use automatic differentiation in our stochastic simulation? This means we can potentially develop extremely complex simulation models and use automatic differentiation to understand the effects of every single model input. In this case, our simulation is fairly simple, but the prospects for this technique are exciting! We also see that our results are close to the values from our prior methods.

Option Value: 5.0926 # sensitivity of option price to:

------------------------ ---------------------------------

Delta: -0.4025 # underlying price

Rho: -45.3420 # interest rates

Vega: 38.4292 # volatility

Theta: 1.8899 # time

Epsilon: 40.2495 # dividend rate

Strike Sens: 0.4534 # strike price

Results

Let's look at the results from each of the four methods, focusing on option value, greeks, and run time on my local CPU.

Formula Numerical Auto-Diff Monte Carlo*

Option Value: 5.0885 5.0885 5.0885 5.0926

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Delta: -0.4026 -0.3907 -0.4026 -0.4025

Rho: -45.3458 -45.2968 -45.3458 -45.3420

Vega: 38.4103 38.4164 38.4103 38.4292

Theta: 1.8883 1.8803 1.8883 1.8899

Epsilon: 40.2573 40.2069 40.2573 40.2495

Strike Sens: 0.4535 0.4654 0.4535 0.4534

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Run Time: 0.535 ms 1.140 ms 0.489 ms 5.160 ms

* 100,000 scenarios

The first three methods arrive at the same option price because we used the Black-Scholes formula each time. The first column greeks are the "true" sensitivities with respect to each of the inputs, derived directly from Black-Scholes. We can see that PyTorch automatic differentiation (column 3) was able to exactly reproduce those values in roughly 10% less time! What's more impressive, however, is that automatic differentiation takes less than half the time of the finite difference method.

The derivatives from finite differences (column 2) are slightly different than the "true" values because they are based on 1% jumps from baseline option value. In fact, they capture some of the convexity of the option value. This may or may not be useful depending on how the greeks will be used. For example, if we were hedging a large portfolio of options, then the differences in delta (-0.4026 vs. -0.3907) could impact our hedging accuracy.

Finally, the monte carlo simulation took roughly 10 times longer than the Black-Scholes methods, but that was expected. It likely wasn't necessary to run 100,000 scenarios to converge for a problem like this, so we could shorten run time by reducing that number. Regardless, I'm most impressed with PyTorch's ability to backpropagate derivatives through a stochastic sampler. There are many, many problems that we approach using monte carlo analysis, and I believe automatic differentiation will help us understand the dynamics of those problems much better.