Riddler Cycling

Sep 20, 2019

Introduction

This week's riddler was an entertaining blend of probability and one of my favorite sports, cycling. We're asked to choose the ideal pace for a team time trial - trying to balance the rewards of a competitive time with the risks of pushing our riders too hard and having them crack due to the effort.

You are the coach for Team Riddler at the Tour de FiveThirtyEight, where there are 20 teams (including yours). Your objective is to win the Team Time Trial race, which has the following rules:

- Each team rides as a group throughout the course at some fixed pace, specified by that team’s coach. Teams that can’t maintain their pace are said to have “cracked,” and don’t finish the course.

- The team that finishes the course with the fastest pace is declared the winner.

- Teams ride the course one at a time. After each team completes its attempt, the next team quickly consults with its coach (who assigns a pace) and then begins its ride. Coaches are aware of the results of all previous teams when choosing their own team’s pace.

Assume that all teams are of equal ability: At any given pace, they have the exact same probability of cracking, and the faster the pace, the greater the probability of cracking. Teams’ chances of cracking are independent, and each team’s coach knows exactly what a team’s chances of cracking are for each pace.

Team Riddler is the first team to attempt the course. To maximize your chances of winning, what’s the probability that your team will finish the course? What’s the probability you’ll ultimately win?

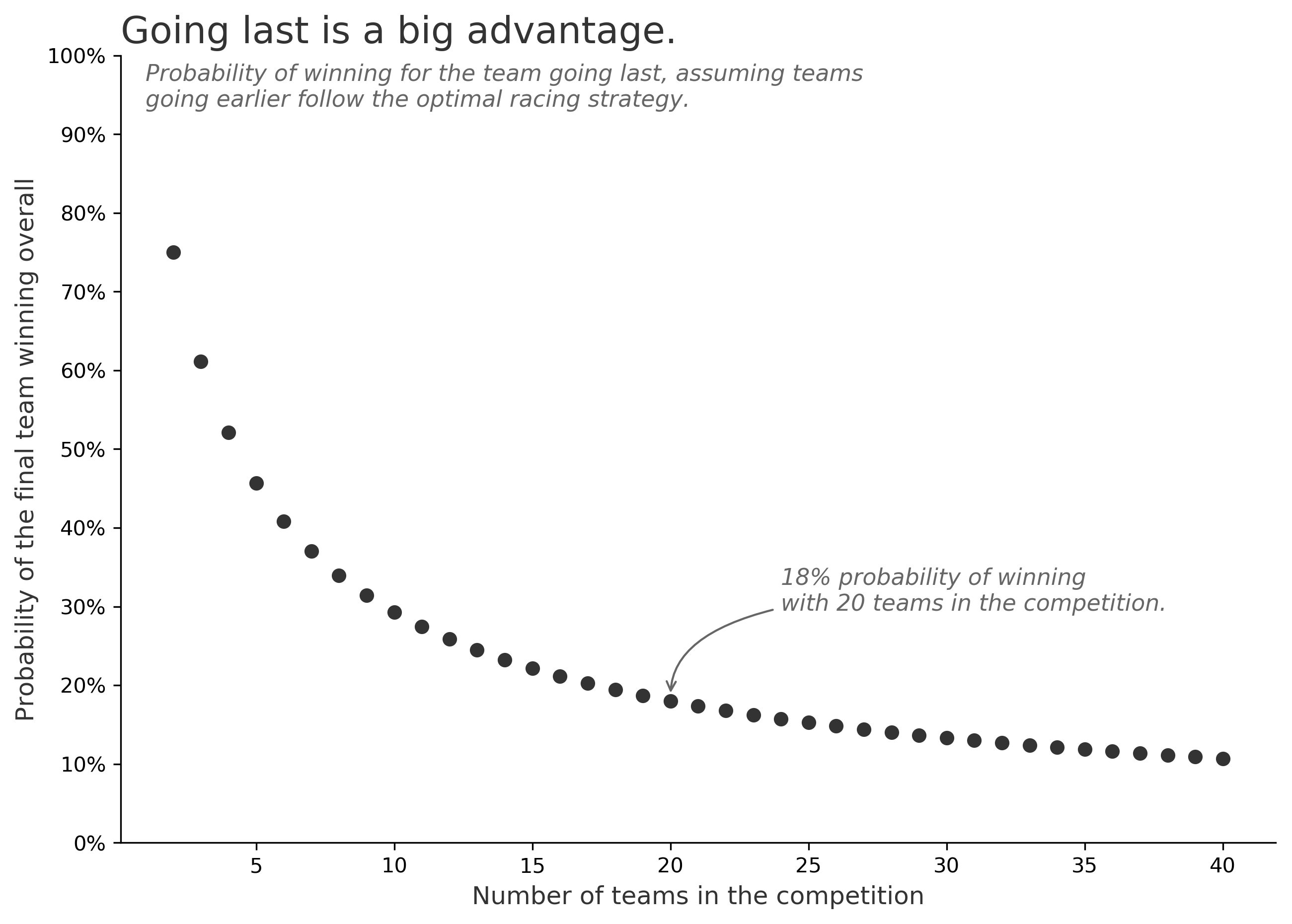

Extra Credit: If Team Riddler is the last team to attempt the course (rather than the first), what are its chances of victory?

Solution

At first, it seems like the problem doesn't give us enough information about the relationship between the pace and the probability of cracking. Wouldn't it be useful to know exactly what pace is associated with the probability of cracking? Is it a linear relationship? Quadratic? Fortunately, we can solve the problem without knowing this - of course the Riddler wouldn't let us down! Let's figure out how.

Let's call the probability of cracking . This value will be a number between 0% and 100%. At 0%, we've selected a pace such that we're guaranteed to finish the course: it might be slow, but we will be sure to complete the race. At 100%, we're guaranteed not to finish the race, so it's impossible for us to win. Some point in between lies the best chance for us to win.

Suppose we pick a value of . If we complete the race, our competitors will choose a probability of cracking that is slightly higher, resulting in a pace that is slightly faster. If they also complete the race, they will move ahead of us in the rankings. This will continue for each subsequent team. On the other hand, if we fail to complete the race, then our competitors could choose any new value of they want, but it won't matter for us, because we would already have been eliminated.

Therefore, we win the time trial if and only if two things happen:

- We complete the race successfully at our desired pace.

- Each of the 19 subsequent teams fails to complete the race with at least the same pace we set.

If we express this mathematically, our odds of winning, , look like this.

This equation has the two components we want: our probability of finishing the race, given by , and the probability of each competitor failing to complete the race, given by . To find the value of that maximizes this function, we use calculus: take the derivative, set it to zero, then solve for . This tells us the point at which the function stops rising or falling, which means it is either a minimum or a maximum.

We use the chain rule to differentiate , which gives us the following:

When we set to zero and simplify the terms on the right, we get:

which evaluates to:

and finally:

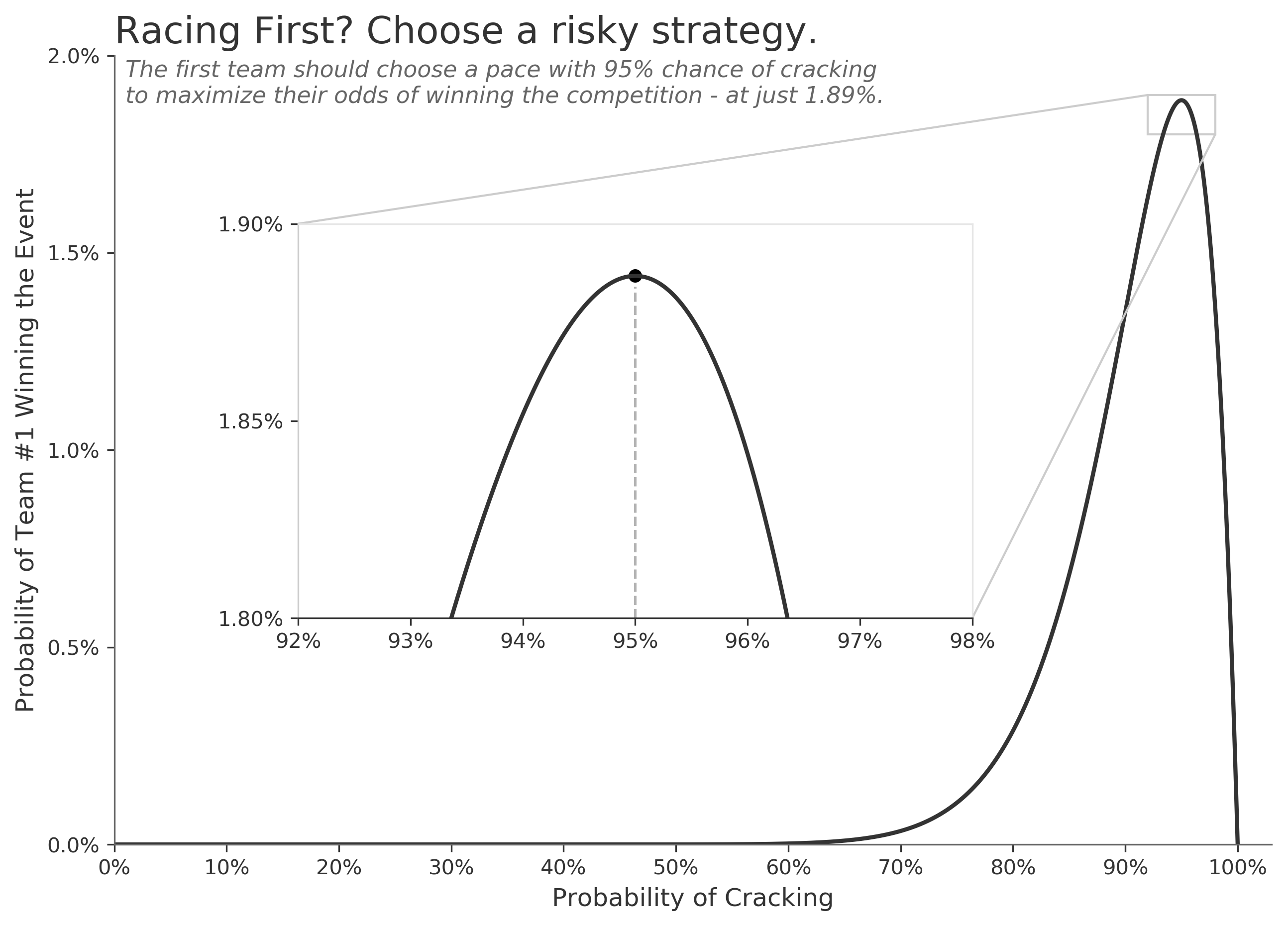

Therefore, the value of that maximizes our odds of winning is . When we choose 95% for , our overall chances of winning the event are . In other words, we should pick an extremely risky strategy with a low probability of success in order to have the best odds of winning the entire event. Our odds of completing the time trial are low, but so are everyone else's! As we can see in the chart below, the function hits a maximum value at 95%.

Extra Credit

There's a nice feature of our answer above. The value of corresponds exactly with the number of teams in the competition. In fact, for a race with teams, the team going first should always race with . (For example, the first team in a 10-team field should select as their value of .) Subsequent teams will race with values of that depend on what has happened before. They will either race at the highest successful attempt so far, or the value of they would select as if they were racing first in a brand new event.

In our race, with 20 teams, the table below shows the values of that each team would select, as long as no prior team has completed the race. For example, the fifth team would select a value of if no prior team had finished. If a prior team had finished, the fifth team would select the value of set by that prior team. The final team, with the advantage of seeing everyone's scores before competing, could potentially select a value of if nobody had successfully finished the race - guaranteeing a finish and a win. Otherwise, they would select the value of from the last team that finished.

| Team (n/20) | Ideal | ... | Team (n/20) | Ideal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 95.00% | 11 | 90.00% | |

| 2 | 94.74% | 12 | 88.89% | |

| 3 | 94.44% | 13 | 87.50% | |

| 4 | 94.12% | 14 | 85.71% | |

| 5 | 93.75% | 15 | 83.33% | |

| 6 | 93.33% | 16 | 80.00% | |

| 7 | 92.86% | 17 | 75.00% | |

| 8 | 92.31% | 18 | 66.67% | |

| 9 | 91.67% | 19 | 50.00% | |

| 10 | 90.91% | 20 | 00.00% |

Now we have the tools we need to answer the extra credit problem. Suppose team 1 completes the race, which happens 5% of the time. Every subsequent team would be forced to attempt (almost exactly) the same pace, and team 20 would win the overall competition only if they are able to complete the course as well with the same value of , which occurs (almost exactly) 5% of the time. The total odds of this happening are . If team 1 fails their attempt, then we would move to team 2, which would choose a value of . If they succeed, every subsequent team would attempt the same pace, all the way until team 20. This pattern continues for all teams.

To calculate the odds of team 20 winning the competition, we must account for each of these branching paths, summing the probabilities along the way. We will use the operator to show the maximum probability that team 20 wins, by assuming they attempt exactly the same as prior successful teams.

A formula like this lends itself to a recursive implementation using code. With 20 teams, the team going last has at most a 17.99% chance of winning overall.

def model(teams=20):

"""

Solves the extra credit portion of

the Riddler Classic from 9/20/19

"""

if teams == 1:

# if there is only one team,

# they win 100% of the time!

return 1.0

else:

# multiple teams; calculate the

# odds of the last team winning

return (1/teams)**2 + (teams-1)/teams*model(teams-1)

>>> model(20)

0.17988698285718413

Finally, we can plot the win percentages for the team going last among a competition with competitors. It's a remarkable advantage to go last!