Riddler Pennies

Jan 24, 2020

Introduction

This week's Riddler Classic explores ideal strategy in a two-player game. We take turns removing coins from two piles, and the last one to remove a coin wins. I'll use pen and paper to sketch out the logical framework, then code a flexible solution using python and dynamic programming.

The game starts with somewhere between 20 and 30 pennies, which I then divide into two piles any way I like. Then we alternate taking turns, with you first, until someone wins the game. For each turn, a player may take any number of pennies he or she likes from either pile, or instead take the same number of pennies from both piles. Each player must also take at least one penny every turn. The winner of the game is the one who takes the last penny.If we both play optimally, what starting numbers of pennies (again, between 20 and 30) guarantee that you can win the game?

Solution

I'll take a small liberty and answer the complementary question: what configurations of pennies guarantee that I lose the game? There are fewer combinations that satisfy this constraint, so it's easier to list them.

With their choice of 20-30 pennies, my opponent could create three configurations that guarantee I lose the game, provided I must play first: (8, 13), (9, 15), and (11, 18). These configurations require 21, 24, and 29 pennies, respectively. If my opponent starts with any other number of pennies between 20-30, there is no configuration they could create that I can't win by playing optimally.

Methodology

I used a combination of pen and paper and computer code to solve this problem. I started by looking for patterns in a highly simplified version of the game, then I generalized those patterns to larger numbers of coins. In computer science this approach is called dynamic programming, where we solve a complex problem by breaking it down into simpler component parts that we can solve individually. Later, we'll reuse the simple component parts to solve the more complex problem, like building a lego structure with little bricks that we solve along the way.

Without loss of generality, I will follow the convention that (, ) represents the state of the game, where , so the smaller pile is always listed first. I will assign winning states a value of 1, and losing states a value of -1. The simplest sub-problem we can solve is a game with one coin, where and . In this sub-problem, we can win immediately by taking the only coin available, so the expected value of (0, 1) is 1.

The next sub-problem involves two coins, and we have two states: (0, 2) or (1, 1). With (0, 2) we can win immediately by taking both coins from pile . With (1, 1), we can win immediately by taking one coin from each pile. The expected values of (0, 2) and (1, 1) are both 1.

With three coins, we also have two states: (0, 3) or (1, 2). (0, 3) has a winning move by taking all three coins from pile , so its expected value is 1. However, (1, 2) is more complicated. Let's list all available moves from this position:

| Begin State | Move | End State | Expected Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1, 2) | (1, 0) - take 1 coin from | (0, 2) | 1 |

| (1, 2) | (0, 1) - take 1 coin from | (1, 1) | 1 |

| (1, 2) | (0, 2) - take 2 coins from | (0, 1)* | 1 |

| (1, 2) | (1, 1) - take 1 coin from both piles | (0, 1) | 1 |

| *recall we always set |

Each of our available moves results in a state with expected value 1... for our opponent! We can't make any move that avoids losing from this position, so the expected value of (1, 2) is -1.

Each state we solve gets added to a dictionary of states and expected values. To solve states with larger numbers of coins, we follow a process like this:

- List all the available moves we could make.

- Determine the resulting states after we make each possible move.

- If we've calculated the value of the new state before, use it. Otherwise, go to step #1 with the new state. At each change of turns, multiply the expected values by -1.

- Out of all possible moves, choose the best one - the one that produces an expected value of 1 - if possible. Otherwise, mark the state as losing.

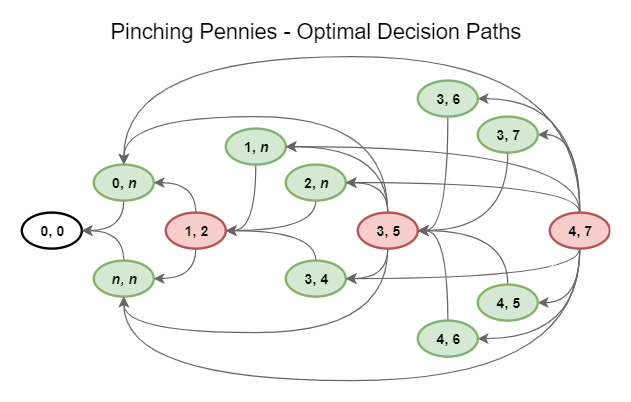

If we continue this process by hand, we can build a small diagram of optimal decisions, shown below. Each state has a color: red states are losing, and green states are winning. To simplify the states, I've used a generic to represent some positions. (0, ) represents a state with a zero in one pile and any number of coins in the other. Similarly (, ) represents a state with an equal number of coins in both piles. For example, we showed that no move from (1, 2) can win the game, because (1, 2) only connects to (0, ) and (, ), which are winning states for our opponent.

Suppose we start at (3, 7) on our turn. Our best move is to remove 2 coins from pile , putting our opponent in the unwinnable state (3, 5). The opponent may choose to remove one coin from pile , giving us the state (3, 4). We will remove 2 coins from both piles, giving our opponent the unwinnable (1, 2) state, from which we've shown we will eventually win.

As the diagram shows, this process quickly becomes complicated for larger numbers of coins. At this point I turned to the computer. In python I created a class called GameState that tracks the number of coins in each pile and allows us to simulate potential moves and calculate expected values using the steps listed above. For example, we can verify the expected values we calculated by hand earlier, and test states with much higher values.

>>> GameState(a=1, b=1).expected_value()

1

>>> GameState(a=1, b=2).expected_value()

-1

>>> GameState(a=75, b=90).expected_value()

1

We can also use the GameState class to identify the best move to make from any state. For example, how should we play if there are 75 coins in pile and 90 coins in pile ?

>>> GameState(a=75, b=90).best_move()

(51, 51)

The best move is to remove 51 coins from both piles. (Note, there may be several winning moves from a given position, but the code returns the move that wins the fastest. No need to delay the inevitable...) After our move, the opponent faces a new GameState with and . What is our opponent's best move?

>>> GameState(a=24, b=39).best_move()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError: No best move; this is a losing position

Good news for us! Looks like no matter what our opponent does, we are guaranteed to win.

Finally, to answer the original question, we want to list all unwinnable states. Because we store all the expected values, we can search the dictionary for all the losing states and return them as a list.

>>> # show the first 20 losing states

>>> GameState.losing_states()[:20]

[GameState(a=0, b=0),

GameState(a=1, b=2),

GameState(a=3, b=5),

GameState(a=4, b=7),

GameState(a=6, b=10),

GameState(a=8, b=13),

GameState(a=9, b=15),

GameState(a=11, b=18),

GameState(a=12, b=20),

GameState(a=14, b=23),

GameState(a=16, b=26),

GameState(a=17, b=28),

GameState(a=19, b=31),

GameState(a=21, b=34),

GameState(a=22, b=36),

GameState(a=24, b=39),

GameState(a=25, b=41),

GameState(a=27, b=44),

GameState(a=29, b=47),

GameState(a=30, b=49)]

We use this list to answer the original question. With 20-30 coins, only the states (8, 13), (9, 15), and (11, 18) guarantee us to lose if we play first. Of course we can test larger numbers of coins, but I'll leave that as an exercise for the motivated reader. My full code is available below!

Full Code

The code for this week was fun to write. I created a class called GameState that represents the game, has methods to yield valid moves, calculate expected value, return the best move to make, and more. I feel like I could have kept adding more and more functionality to this class, but I tried to keep it relatively focused for now.

from collections import namedtuple

from itertools import chain

class GameState(namedtuple("GameState", "a b")):

"""

Each turn of the game we may take any number of pennies from either pile, or

an equal number of pennies from both piles. (We must take at least one penny

per turn.) The person who takes the last penny (or pennies) wins the game.

Represent the state of the game as a tuple, (a, b), where a is the number of

pennies in the first pile, and b is the number of pennies in the second pile

If a == b, then the game will end this turn because we will take all pennies

from both piles. If either a or b == 0, then we can also end the game this

turn by taking the remaining pennies from the non-empty pile. Otherwise, we

will determine the optimal action to take by considering all possible moves

and choosing the one that gives the best chance of winning on a later turn.

Examples

--------

>>> # start a game with 8 pennies in "A" and 14 pennies in "B"

>>> # then determine its expected value and best move

>>> game = GameState(8, 14)

>>> game.expected_value()

1

>>> game.best_move()

(0, 1)

"""

_cache: dict = {}

def __hash__(self):

"""

Custom hash function for the GameState, which allows us to assert

equality between GameState(a, b) and GameState(b, a)

>>> GameState(5, 10).__hash__()

3713085962056061156

>>> GameState(10, 5).__hash__()

3713085962056061156

"""

return hash((min(self.a, self.b), max(self.a, self.b)))

def __eq__(self, other):

"""

We want GameState(a, b) to be equal to GameState(b, a)

Examples

--------

>>> GameState(5, 10) == GameState(10, 5)

True

"""

return hash(self) == hash(other)

def __sub__(self, other: tuple):

"""

Update the game state by subtracting pennies

Examples

--------

>>> GameState(9, 10) - (5, 5)

GameState(a=4, b=5)

>>> GameState(10, 5) - (4, 0)

GameState(a=6, b=5)

"""

if other[0] > self.a or other[1] > self.b:

raise ValueError("Not enough pennies left to make this move.")

return GameState(self.a - other[0], self.b - other[1])

def available_moves(self):

"""

Yield all possible moves for this GameState

Examples

--------

>>> moves = GameState(1, 2).available_moves()

>>> list(moves)

[(1, 0), (0, 1), (0, 2), (1, 1)]

"""

# create separate generators for all moves taking coins from pile a,

# pile b, and equal draws from both piles, then chain them together

gen_a = ((x, 0) for x in range(1, self.a + 1))

gen_b = ((0, x) for x in range(1, self.b + 1))

gen_c = ((x, x) for x in range(1, min(self.a, self.b) + 1))

return chain(gen_a, gen_b, gen_c)

def best_move(self) -> tuple:

"""

Return the best possible move to make; if there are multiple best

moves, return the one that removes the most pennies from the board

Examples

--------

>>> GameState(9, 10).best_move()

(8, 8)

>>> GameState(2, 1).best_move()

Traceback (most recent call last):

ValueError: No best move; this is a losing position

"""

winning_moves = (

move for move in self.available_moves()

if (self - move).expected_value() == -1

)

try:

return max(winning_moves, key=sum)

except ValueError as e:

raise ValueError("No best move; this is a losing position") from e

def expected_value(self) -> int:

"""

Returns the expected value from this GameState, assuming it is your

move. 1 represents a guaranteed win with a single move or series of

moves, while -1 represents a guaranteed loss.

Examples

--------

>>> GameState(1, 3).expected_value() # winning state

1

>>> GameState(2, 2).expected_value() # winning state

1

>>> GameState(1, 2).expected_value() # losing state

-1

"""

# check the cache to see if we've already calculated the result

# otherwise, calculate the result and store it in the cache

try:

return self._cache[self]

except KeyError:

if self.a == self.b == 0:

self._cache[self] = -1

else:

self._cache[self] = max(

-1 * (self - move).expected_value()

for move in self.available_moves()

)

return self._cache[self]

@classmethod

def losing_states(cls, max_coins: int = 100):

"""

Return all losing states from the cache up to a maximum coin count

Examples

--------

>>> GameState._cache = {} # reset the cache before performing this test

>>> GameState.losing_states(max_coins=8)

[GameState(a=0, b=0), GameState(a=1, b=2), GameState(a=3, b=5), GameState(a=4, b=7)]

"""

# run the GameState up to the max value to populate the cache

GameState(max_coins, max_coins).expected_value()

return [k for k, v in cls._cache.items() if v == -1]

if __name__ == "__main__":

import doctest

doctest.testmod()