Riddler Rolling

Nov 15, 2019

Introduction

This week's Riddler tested our ability to think recursively, but surprisingly not of the coding variety. Instead, we'll use a series of equations to solve the problem analytically. Brings back memories of high school proofs... which I may or may not remember with complete fidelity.

To start the game, you roll the die. Your current “score” is the number shown, divided by 10. For example, if you were to roll a 7, then your score would be 0.7. Then, you keep rolling the die over and over again. Each time you roll, if the digit shown by the die is less than or equal to the last digit of your score, then that roll becomes the new last digit of your score. Otherwise you just go ahead and roll again. The game ends when you roll a zero.For example, suppose you roll the following: 6, 2, 5, 1, 8, 1, 0. After your first roll, your score would be 0.6, After the second, it’s 0.62. You ignore the third roll, since 5 is greater than the current last digit, 2. After the fourth roll, your score is 0.621. You ignore the fifth roll, since 8 is greater than the current last digit, 1. After the sixth roll, your score is 0.6211. And after the seventh roll, the game is over — 0.6211 is your final score.

What will be your average final score in this game?

Solution

The expected value of this game is 9/19, roughly 0.473684.

At first, the problem seems like a deeply nested recursive brain-melter. While that might be true, there is a pattern we can exploit in order to find a clean solution. We'll solve the problem by proving a simple base case, then build upon the base case to solve for the final answer.

The simplest base case we can start with is a game with a one-sided dice. (Indulge me, and suspend your rational faculties for a moment.) In this "game", we will always have a score of zero. Formally, we can say that , meaning the expected value of this game is equal to zero.

Now, let's build on the base case. Suppose we increase the complexity and have a two-sided dice with the numbers zero and one. (One might even say it resembles a coin...) What can happen in this game? We can roll a zero immediately and end with a score of zero, or we can roll a one and continue. If we roll a one, we increment our score in the appropriate decimal place, after which we will find ourselves in a familiar position: we can either flip a zero or a one again.

We can now write an expression for that takes both of these outcomes into account.

With 50% probability, we will receive the expected value of 0 and the game will end. With the other 50% probability we will roll a one and add to our total, then move to the next decimal place, where we will expect to add to our score again. We divide by ten to account for the fact that we move to the next decimal place each time we roll again.

Now, after plugging in , we can solve the equation for . We get .

What about the next case, ? With 33% probability we can roll a zero and end the game; with 33% probability we can roll a one, and we'll find ourselves in the universe again; with 33% probability we can roll a two and stay in the universe.

With some algebra, we can solve this equation for , which gives . See a pattern? It looks like . Let's attempt to confirm by expanding the equation for . For a dice with sides we can expand the formula as follows. For simplicity we'll omit the term because we know it evaluates to zero.

We can factor the 's and 10's from the denominator for a simpler expression:

We will attempt to prove using induction. We've already verified that . Now we must verify that . We will use the fact that to remove the summations from the numerator.

Next, we multiply both sides by :

Now, remove the common terms, and verify both sides are equal.

Therefore we have proven by mathematical induction that . Our original problem was for , so we confirm our answer of .

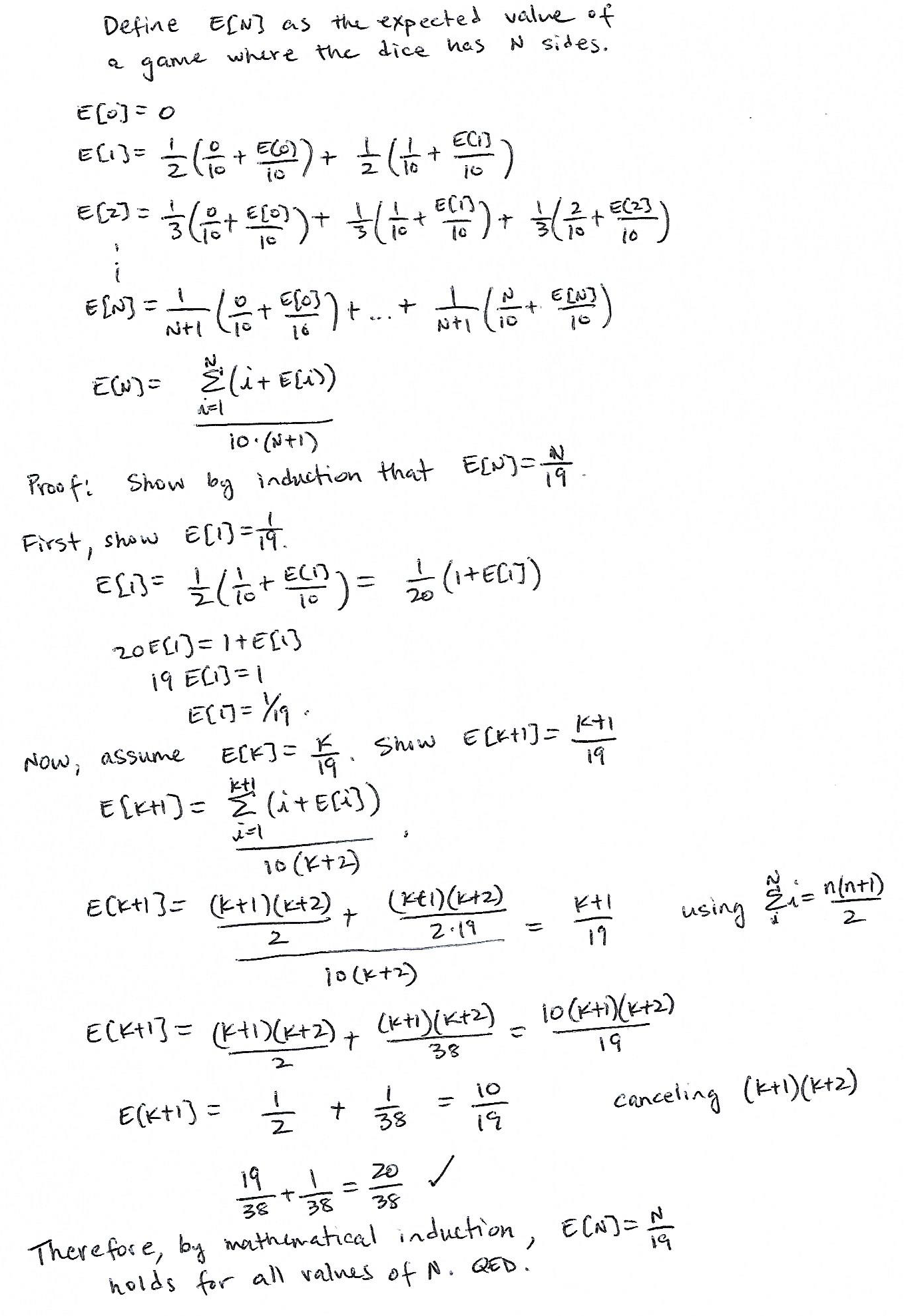

Proof

Because LaTeX is not my specialty, I also wrote an old-fashioned proof as well. Enjoy!